When You’ve Had Too Much

The week between Christmas and New Years is always a bit of a strange feeling. Christmas decorations are still up as a reminder of the joyful season, families begin to disperse and head their separate ways, the most motivated start to plan their resolutions, and we all feel a little full and sluggish from enjoying one too many delicious treats. I certainly know that my family always looks forward to the holiday feasts and most definitely always goes overboard, which leaves us in a perpetual food coma until we can get ourselves back on track. This reminds us that without a doubt you can have too much of a good thing.

The same goes for having too much of a “good” thing in investment portfolios – i.e what we refer to as concentrated positions. A concentrated position can be defined as having more than 5% (some analysts stretch this up to 20%) of investable net worth in one single stock. Another way of defining it is if a major loss in the concentrated position derails your financial plan, then you are too concentrated. Usually, concentration is a result of employer stock compensation or retirement plans, inheritance, or can just be the result of owning a stock that has had exceptional long-term growth, just to name a few. And while I won’t ignore the elephant in the room; the infamous quote from Warren Buffett “Diversification may preserve wealth, but concentration builds wealth.”, holding a significant exposure to one stock increases risk, volatility, and the likelihood of future tax implications.

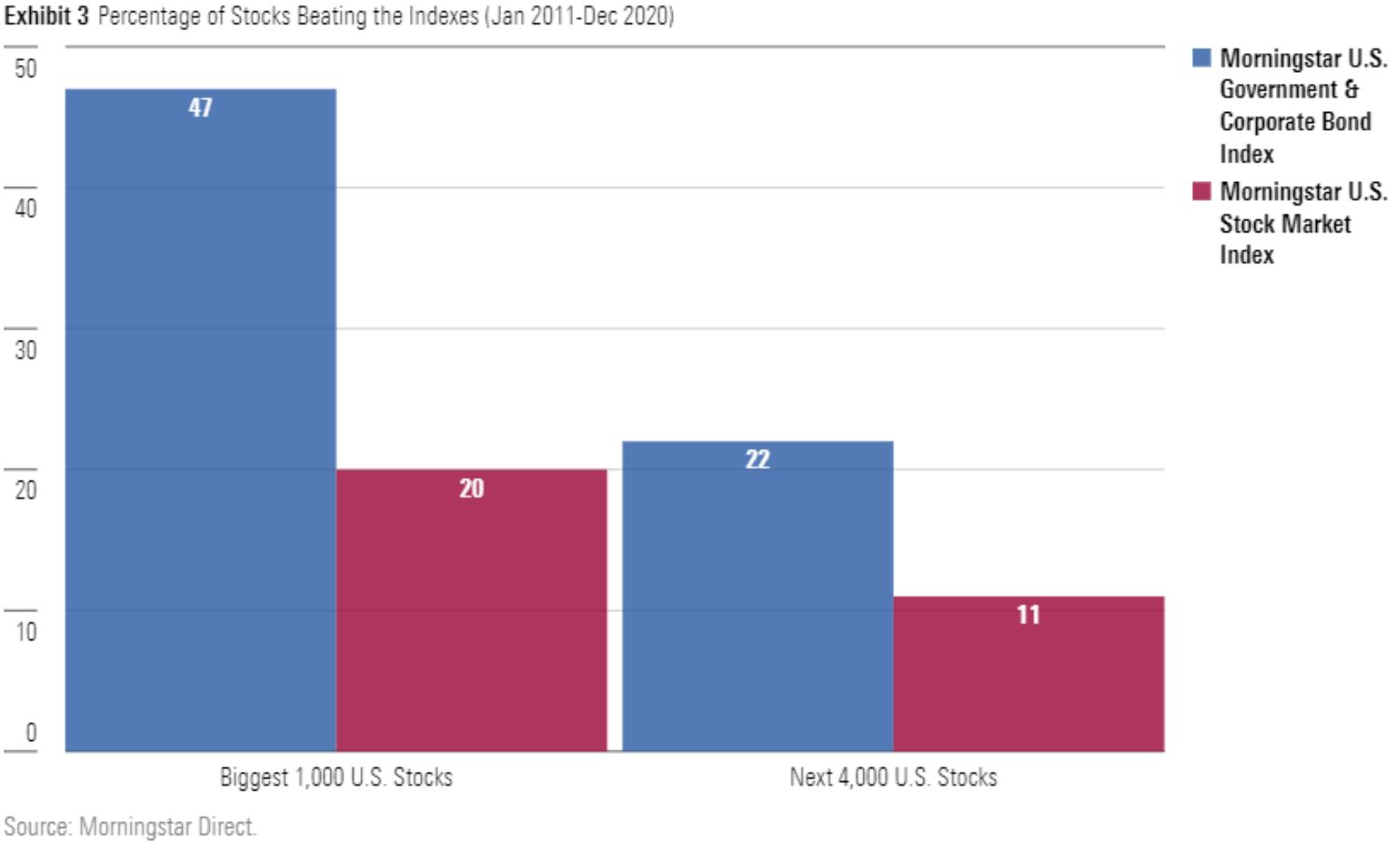

Even further, for the years 2011-2020, only 20% of the largest 1.000 stocks had a higher return compared to their benchmark index and only 11% of the next 4,000 largest stocks beat their benchmark index.

That is a pretty significant risk to take for one company and in my opinion strongly supports the case for diversification. However, one of the greatest reasons investors with concentrated positions don’t diversify outside of realizing substantial capital gains, are emotional / cognitive biases such as the familiarity bias or the endowment effect.

The endowment effect describes a circumstance in which an individual places a higher value on an object that they already own than the value they would place on that same object if they did not own it.

Familiarity Bias – The tendency to make investment decisions based on the lens of: being familiar with the investment option.

These biases tend to immobilize investors from taking prudent action to reduce risks related to the concentrated stock positions.

And while the data above shows there still is a small percentage of companies that have experienced growth over time, it is important not to forget that they have also experienced significant periods of volatility.

Case in point the below chart shows Amazon’s returns versus the drawdown from 1997 until 2016.

So what’s an investor who’s had too much of a good thing to do? There is no one size fits all answer as each investor’s goals, tax rates, needs, and specific situations will vary. However, your financial advisor can work with you to thoughtfully craft a plan together to reduce concentration and increase diversification through a variety of strategies such as gifting, fulfilling charitable donations, tax efficient trading, and integrating estate planning. All of this of course to avoid the proverbial stomach that comes from “overindulgence”!

Wishing everyone a very happy, safe, and healthy(ish) New Year 😊!